Uruguay plan to let gov't sell marijuana — Uruguay's national government said Wednesday it hopes to fight a growing crime problem by selling marijuana to citizens registered to buy it, and will send a bill to Congress that would make it the first country in the world to do so.

Under the plan, only the government would be allowed to sell marijuana and only to adults who register on a government database, letting officials keep track of their purchases over time.

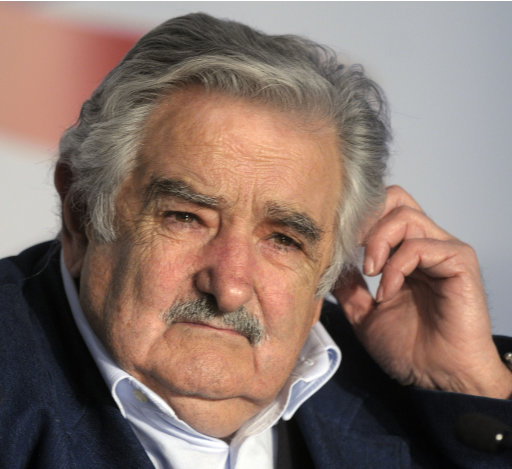

In this Oct. 27, 2011 file photo, Uruguay's President Jose Mujica attends a press conference at the presidential residence in Montevideo, Uruguay. Mujica's government plans to take a step beyond legalizing marijuana. It wants to sell it. Local news media and lawmakers report that the government plans to send a bill to Congress on Wednesday that would legalize marijuana sales as a crime-fighting measure. Only the government would be allowed to sell the marijuana cigarettes, and only to adults registered as users. (AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico, File)

Minister of Defense Eleuterio Fernandez Huidobro told reporters in Montevideo that the measure aims to weaken crime in the country by removing profits from drug dealers and diverting users from harder drugs.

He said the bill would be sent to Congress soon, but an exact date had not been set.

"We're shifting toward a stricter state control of the distribution and production of this drug," Fernandez said. "It's a fight on both fronts: against consumption and drug trafficking. We think the prohibition of some drugs is creating more problems to society than the drug itself."

Uruguayan newspapers have reported that money from taxes on marijuana sold by the government would go toward rehabilitating drug addicts. The government did not provide details.

There are no laws against marijuana use in Uruguay. Possession of the drug for personal use has never been criminalized.

Media reports have said that people who use more than a limited number of marijuana cigarettes would have to undergo drug rehabilitation.

Some Uruguayans wondered how successful such a measure could be.

"People who consume are not going to buy it from the state," said Natalia Pereira, 28, adding that she smokes marijuana occasionally. "They're going to be mistrust buying it from a place where you have to register and they can typecast you."

A debate over the move lit up social media networks in the country, with some people worried about free sales of marijuana and others joking about it.

"Legalizing marijuana is not a security measure," one man in the capital of Uruguay wrote on his Twitter account.

"Ha, ha, ha!" joked another. "I can now imagine you going down to the kiosk to buy bread, milk and a little box of marijuana."

The idea is to weaken crime by removing profits from drug dealers and diverting users from harder drugs.

"The main argument for this is to keep addicts from dealing and reaching (crack-like) substances" such as base paste, said Juan Carlos Redin a psychologist who works with drug addicts in Montevideo. "Some studies conclude that a large number of base paste consumers first looked for milder drugs like marijuana and ended with freebase."

Redin said Uruguayans should be allowed to grow their own marijuana because the government would run into trouble if it tries to sell it. The big question he said will be, "Who will provide the government (with marijuana)?"

"If they actually sell it themselves, and you have to go to the Uruguay government store to buy marijuana, then that would be a precedent for sure, but not so different than from the dispensaries in half the United States," said Allen St. Pierre, executive director of U.S.-based National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, or NORML.

St. Pierre said the move would make Uruguay the only national government in the world selling marijuana. Numerous dispensaries on the local level in the U.S. are allowed to sell marijuana for medical use.

Possession of marijuana for personal use has never been criminalized in this South American country and a 1974 law gives judges discretion to determine if the amount of marijuana found on a suspect is for legal personal use or for illegal dealing.

"This measure should be accompanied by efforts to get young people off drugs," ruling party Sen. Monica Xavier told channel 12 local TV.

But other drug rehabilitation experts disagree with the planned bill altogether. Guillermo Castro, head of psychiatry at the Hospital Britanico in Montevideo says marijuana is a gateway to stronger drugs.

"In the long-run, marijuana is still poison," Castro said adding that marijuana contains 17 times more carcinogens than those in tobacco and that its use is linked to higher rates of depression and suicide.

"If it's going to be openly legalized, something that is now in the hands of politics, it's important that they explain to people what it is and what it produces," he said. "I think it would much more effective to educate people about drugs instead of legalizing them."

Uruguay is among the safest countries in Latin America but recent gang shootouts and rising cocaine seizures have raised security concerns and taken a toll on the already dipping popularity of leftist President Jose Mujica. The Interior Ministry says from January to May, the number of homicides jumped to 133 from 76 in the same period last year.

Overburdened by clogged prisons, some Latin American countries have relaxed penalties for drug possession and personal use and distanced themselves from the tough stance pushed by the United States four decades ago when the Richard Nixon administration declared the war on drugs.

"Out of all the drugs that are used for psychoactive effect, this is the least toxic, and the least potential for harm," said Lester Grinspoon, associate professor emeritus at Harvard Medical School.

"It may take some time to find a regulatory system that everyone can be comfortable with," Grinspoon added of Uruguay's proposed sale of the drug.

"There's a growing recognition in the region that marijuana needs to be treated differently than other drugs, because it's a clear case that the drug laws have a greater negative impact than the use of the drug itself," said Coletta Youngers, a senior fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America think tank. "If Uruguay moved in this direction they would be challenging the international drug control system." ( Associated Press )

No comments:

Post a Comment